Even though deaf* persons are represented in popular culture more than ever before, there are still misunderstandings and misconceptions about the Deaf community among the hearing population. Despite the slowly growing awareness, many deaf people continue to experience prejudice and discrimination in their daily lives. Audism is still as real as any other form of discrimination and needs to be addressed on both national and international levels.

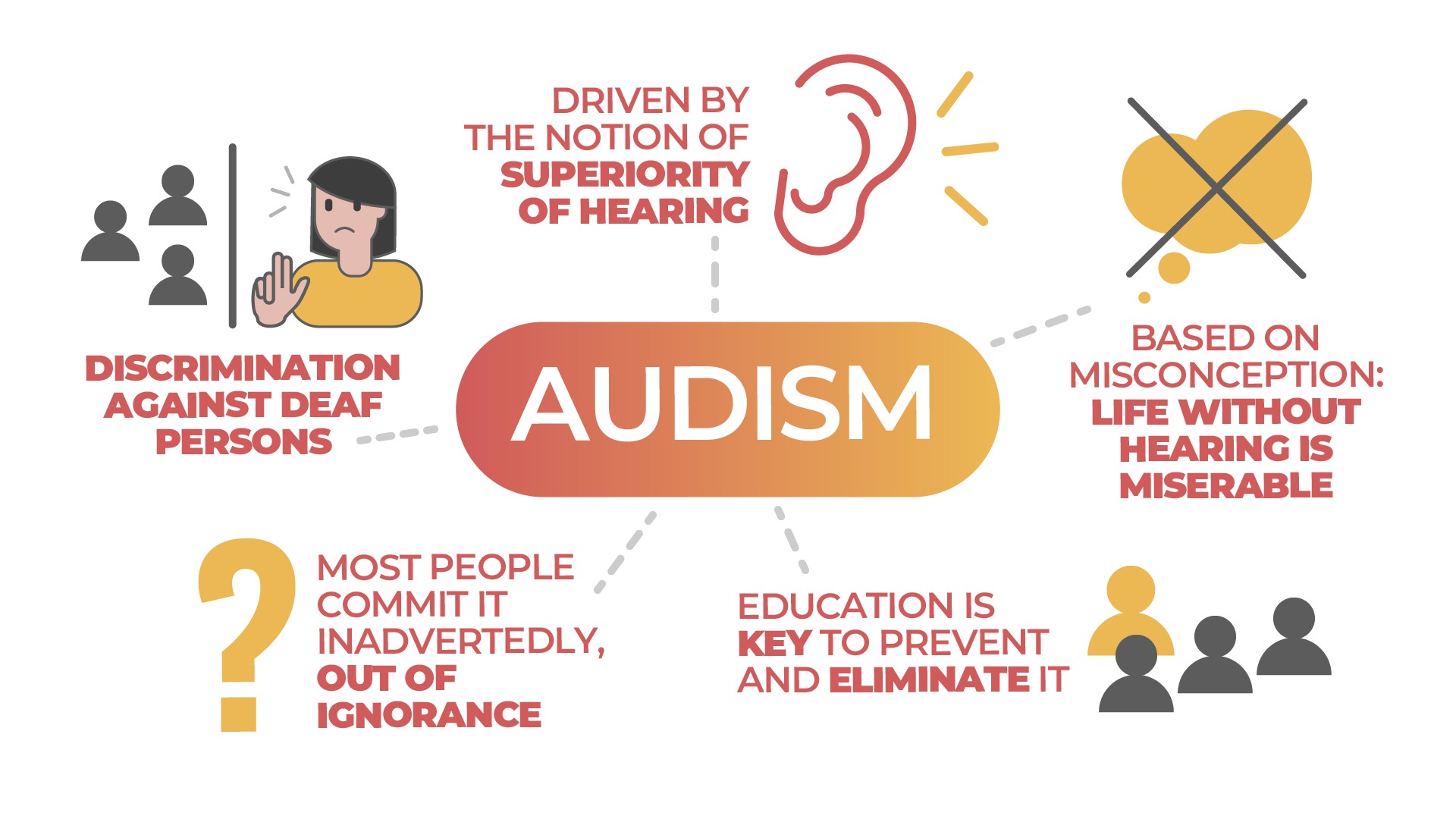

The term ‘audism’ was coined in 1975 in an article written by an American communication and language researcher, Tom L. Humphries as a way to describe discrimination against deaf persons. Audism can take a variety of forms, such as communication discrimination, various assumptions about what deaf persons need or can or cannot do, excluding deaf individuals from social or work environments, etc.

*deaf and Deaf: We use the lowercase when referring to the audiological condition of not hearing, and the uppercase when referring to a particular group of deaf people who identify with and participate in the language, culture, and community of Deaf people.

The many faces of audism

Some of the factors that drive audism are the notion that one is superior based on one’s ability to hear and the common misconception that life without hearing is miserable. But the majority of people commit audism inadvertently – they do not have negative feelings towards the Deaf community and commit audism simply out of ignorance. Regardless of the reasons, education is key to eliminating and preventing deaf discrimination. Below are some examples of audism to be aware of so that we can all be more welcoming towards the Deaf community.

- Assuming that deaf people cannot speak. Some deaf people do speak with their voices, and those that don’t can express themselves just as well using sign languages.

- Not making any effort to communicate or assuming it is solely the deaf persons’ duty to facilitate communication. Finding the best communication method should be a joint effort. When meeting a deaf person, do not make assumptions about their communication and simply inquire about their individual needs. Writing, speech/lip reading, sign language, machine translation technology, hiring an interpreter are all possibilities that can be explored.

- Asking a signing person to “tone down” their facial expressions because they are making others uncomfortable. The system of facial expressions in sign languages is very complex and sign language users heavily rely on it to express both linguistic information and emotions. For example, eyebrow raise is necessary to mark general questions in most sign languages.

- Refusing to explain to a deaf person why everyone around them is laughing/what others are talking about. “I’ll tell you later, it’s not important.” is not a great answer. We all deserve to understand what is happening around us.

- Viewing hearing people and hearing culture as superior to deaf people and Deaf culture. Deaf people have made countless contributions to society. Just think about Liisa Kauppinen, Thomas Edison, and Ludwig van Beethoven.

- Parents of deaf children insisting that they conform only to the hearing culture at the expense of their unique sense of belonging to Deaf culture. Studies show that early immersive exposure to a natural language is crucial to the neurocognitive and linguistic development of any child. And for most deaf children, access to sign language fulfills this vital need since unhindered access to a spoken language is not possible.

- Lowered expectations. Educators have historically held low expectations for the potential of deaf individuals, especially with regards to literacy development and employment, even though deafness in itself does not impair cognitive development. Research demonstrates correlations between expectations and achievements among students in elementary through higher educational settings. High expectations are therefore a necessary component of deaf youths’ education, and their opportunities should not be viewed as limited.

- Using expressions, such as ‘to turn a deaf ear to’, ‘silence is deafening’, ‘are you deaf?’, among many others. The ableist language used to marginalize people with disabilities shows up in many different ways: as metaphors, jokes, or euphemisms. Changing our vocabulary and eliminating those prejudicial expressions is a simple fix that can have a big, positive impact.

What does the Deaf community have to say about audism?

These were just a few examples of audism that deaf people encounter in their everyday lives. Such situations, especially if they happen repeatedly can have a truly damaging impact on the quality of their lives. That’s why it is of utmost importance that the hearing population remains sensitive to the issue and educate themselves about Deaf culture. To make the learning experience more valuable, we asked Deaf community members about their experiences. Here is what they shared with us.

What is an example of audism that you encounter in everyday life?

Barbara: «During conversations at work, my colleagues who know sign language communicate with each other using their voice, even when I am there. This means I cannot follow what they say, and when I ask what they are talking about, they often say “I will tell you later.” Then, I always get very short summaries. They could just use sign language so that I could follow along. I’m always the last one to get information or even no information at all.»

Davy: «Hearing people often stereotype deaf people and their capabilities, even so-called “experts”. Too often, I have been judged as having lesser capabilities or knowledge than my hearing peers. Not every deaf person is the same. To give an example: when I had just finished my education and went out to look for a job, I was forced to go to a ‘specialized’ job center for deaf people. I told the person that was assigned to help me that I wanted to get an administrative job. They immediately answered with: “You are not going to be able to do that because your language skills are too weak.” They did not even ask me anything about my education or skills, they just immediately (incorrectly) labeled me as having weak language skills. If they took the effort to just ask me some questions beforehand, they would have known that I’ve studied languages in school and that I am multilingual.»

Frankie: «What comes up frequently in my everyday life is the tendency of others to “decide” for me. When I was a student, I shared my future plans, namely to study law at a university. Some people spontaneously reacted by telling me that this was impossible, simply because I was deaf, even if I had potential. Another example, intervene by answering for me when I am asked a question without giving me the time to react or considering my feelings. Although it is well-intentioned, the “paternalistic” attitude is generally frowned upon.»

During your lifetime, have you noticed any positive changes with regards to barriers and/or discrimination?

Barbara: «More interest in sign languages, more sign videos on the internet with the inclusion of deaf interpreters, more interpretation from the federal government since COVID-19.»

Davy: «The biggest evolution that I witnessed is the quality of education that deaf people receive. When I was a child, there were only a few deaf people that received higher education. In older generations, like one of my parents, almost all deaf people were ‘forced’ to go into the labor market. Young generations of deaf people graduate in a lot of different areas of higher education and have a lot of possible careers.»

Frankie: «The growing interest in and respect for sign languages.»

What should a hearing person never say to a deaf person?

Barbara: «You are lucky that you are deaf, it’s so loud here» or «Oh, poor you, you can’t hear”».

Davy: «Can you speak? How much do you hear? These are some of the questions I get the most often. It feels like that the hearing people want to know to what grade I do fit in “their” world of sounds as if being able to speak or hear a bit gets me points and makes me a “better” human.»

Frankie: «Are you allowed to drive? *Laugh*»

Many people commit audism inadvertently. Could you share some examples of discrimination that could help the average hearing person avoid committing it?

Barbara: «When introducing a deaf person, many hearing persons first mention that it is a deaf person, and then provide their name or a description of who the deaf person is. Why does the fact that the person is deaf come first?!»

Davy: «Letting deaf people ‘wait a bit’ to get information, and then give a short summary of the information later. And if deaf people say they want the information now, we are seen as nagging.»

Frankie: «Expecting any effort to communicate, to adapt, to come exclusively from us, the deaf. I think life would be much easier if everyone did their bit.»

As you can read, the Deaf community faces many kinds of barriers on a daily basis. Some are physical, some systemic, while others are simply attitudinal. The latter is the most powerful as it gives rise to the first two. It is also the one that we (every one of us!) have the biggest control of. By changing our attitudes and educating ourselves, we can eliminate audism. Will you join us on this mission?

Follow our #DidYouKnowThat campaign to raise your Deaf awareness.

Next article:

deaf of Deaf?